After spending a decade building games for the so-called casual audience, changing course to work on a behemoth like Stellaris has at once been inspiring, academic and humbling for me. While most of the design philosophies I’ve acquired in my career so far have been surprisingly transferable to this new genre, a lot of the practical aspects have to be relearned. In the settling dust of my scuffle with the grand strategy giant, one of the most interesting insights that has crystallized from the chaos was a newfound understanding of Paradox’s fascination with the player-driven fantasy.

The Player-Driven Narrative

Unlike most games where you learn to play the game at the same rate you uncover the narrative, Paradox games throws you into complex, unforgiving, and usually historically accurate scenarios: A French general in World War II, or a Swedish King in the middle ages. There is no fixed path or story - the player starts in the thick of the geopolitics and conflicts their chosen role embodies, and are expected to carve their way out of it, all the while creating a trail of blood called an emergent story.

As a result, fans come to these games with fantasies they want to play out, instead of slipping into a character supplied by the game. This both empowers veterans who come with the right motivations, and confuses newcomers who were expecting the game to provide one.

This was fascinating to me, primarily because it goes against every lesson I’ve learned as a game designer. I had assumed the player to be a blank slate, ripe to be impressed upon with new ideas. It made sense when Raph Koster said that learning a new game was fun and when Jenova Chen explained it to be an incremental process. The idea that a player would use a game as a tool for playing out prepared fantasies, was something I’d thought only happened to flight simulators.

In retrospect, I guess it wasn’t entirely surprising. Every fantastical imagining of the interactive medium uses it in that way, from Janet Murray’s titular introductory chapter in Hamlet on the Holodeck, to the entire premise of Ready Player One. But one particular text was surprisingly relevant, Game Design as Narrative Architecture by Henry Jenkins.

Narrative Architecture

Although Jenkins wrote the essay with level design in mind, it’s startling how much of it applies to Paradox’s user-interface-heavy grand strategy titles. Jenkins talks about the similarities between level design in games and theme park design, and that both create immersive narrative experiences in four ways: evocative spaces, enacting stories, embedded narratives and emergent narratives.

Evocative Spaces

Jenkins explained that theme parks attractions “build upon stories or genre traditions already well-known to visitors”, so that designers can “paint their worlds in fairly broad outlines and count on the visitor/player to do the rest.”

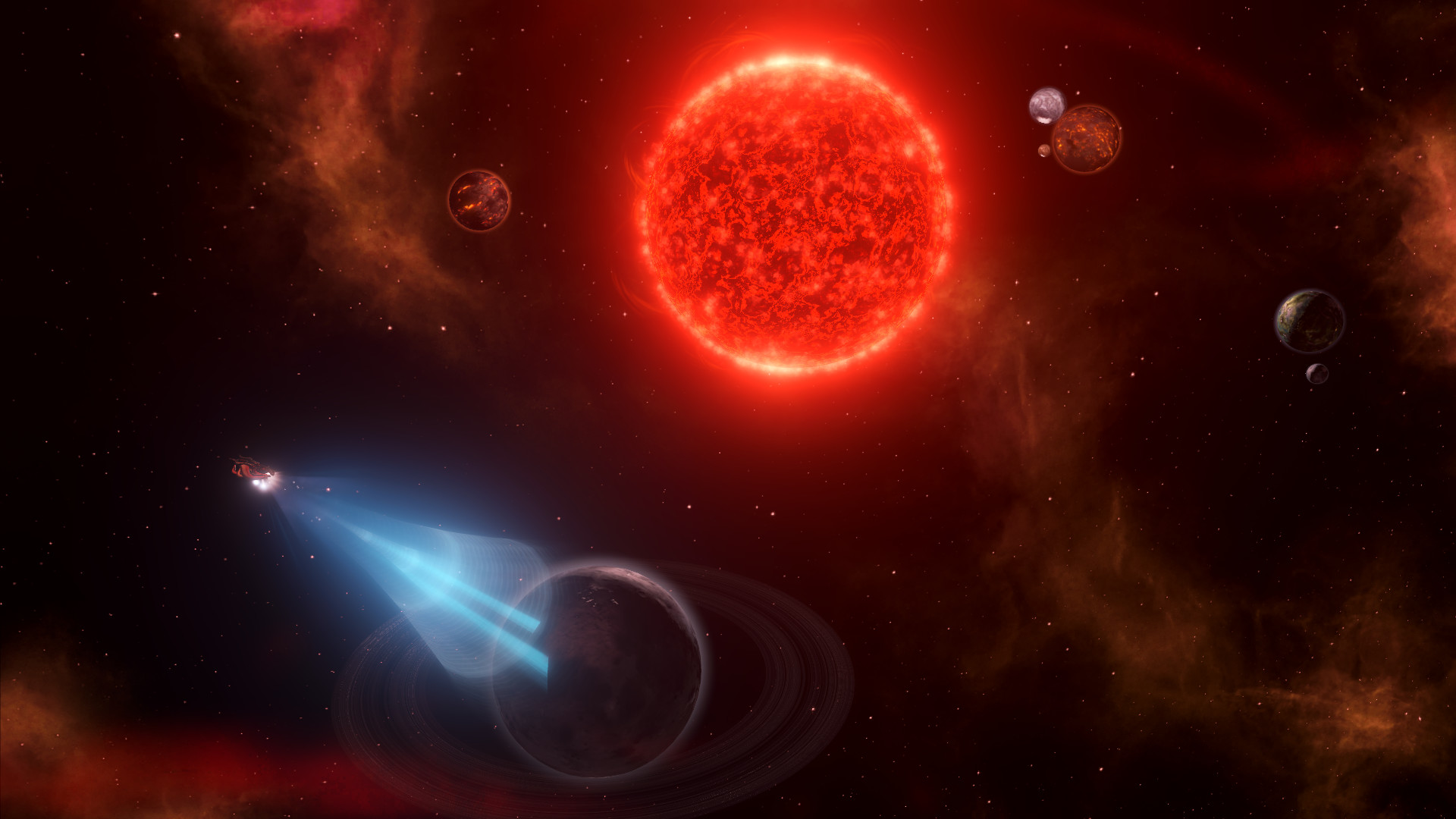

If you take a close look at the stable of successful grand strategy titles produced by Paradox, you’ll notice that there is nothing narratively original about them — and that is their strength. From the medieval court politics of Crusader Kings to the futuristic space battles of Stellaris, Paradox has always relied upon ubiquitous themes and tropes that invites its audience to come prepared with their own related imaginings.

The almost-cliché backdrop of Paradox’s games act as the player-imagination-powered glue that joins all the pieces together. If Crusader Kings had taken place in an original fantastical landscape inhabited by the Urkcaluus and Obabuludadacai, who communicated using pheromones, and relationships between rulers were determined by how many pheromone-filled ritualistic dances you organized every 78 days, it probably wouldn’t have worked as well. I think.

Enacting Stories

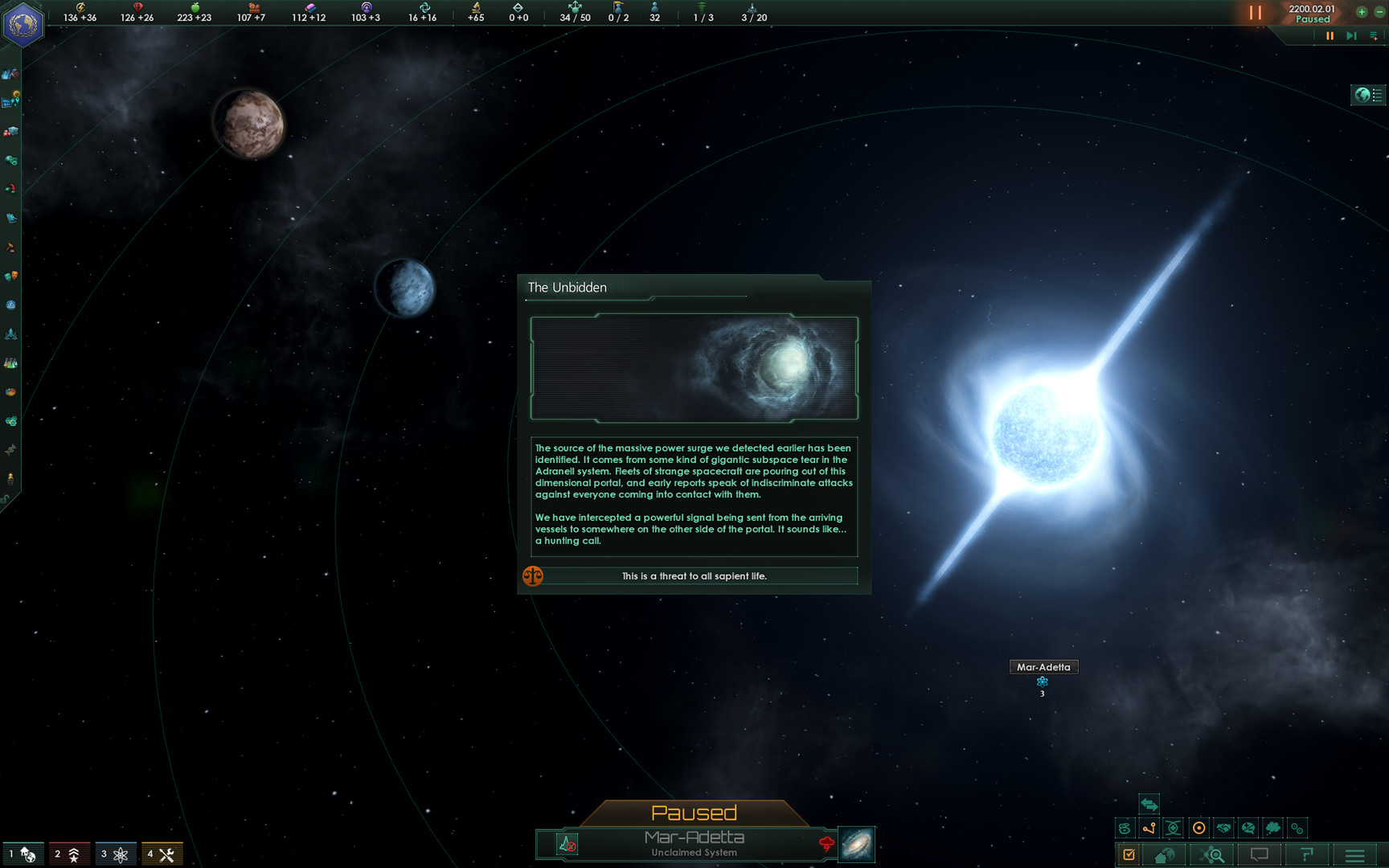

Upon the stage built by these evocative spaces, Jenkins describes short stories being told that “become compelling on (their) own terms without contributing significantly to the plot development”, they could also be “reordered without significantly impacting (the player’s) experience as a whole.”

The event system found in many of Paradox’s grand strategy titles work in this exact way, most of them even furthering the suspension of disbelief by contextualizing the stories with names of characters and places relevant to the player’s current narrative landscape. Consider the text from Stellaris’ Horizon Signal event:

“Science Officer [scientist name] reports that the signal was unexpectedly easy to decipher… but the team has spent considerable time confirming that it was not a hoax. It is a repeating, half-coherent message in the [empire adjective] language - something like a poem. It repeats the phrases GRAVITY IS DESIRE and TIME IS SIGHT. It encodes co-ordinates near the black hole. And it ends with a dedication by name to the Science Officer - who adds dispassionately that they have confirmed that the signal has been radiating into interstellar space before their birth. It fact, the signal may predate our civilization.”

A player could encounter this event at the beginning, middle or end of their play-through without much consequence to the narrative continuity, with characters and entities they recognize roped into the story to lend it extra believability and coherence to the unfolding chains of events.

Embedded Narratives

Comparing narratives in games to traditional stories, Jenkins observed that a game narrative is “less a temporal structure than a body of information”, and that a game designer can “control the narrational process by distributing the information across the game space”. A player can then “reconstruct the plot through (their) acts of detection, speculation, exploration, and decryption”.

This pretty much describes the storytelling process of Paradox’s games, especially Crusader Kings.

If a ruler goes to war with your kingdom, or if someone rejects your proposal for marriage, you can always find the reason (or deduce one) from the exhaustive layers of information available in Crusader King’s tool-tips and user interface dialogs. It usually comes down to a character’s opinion of you, which is in turn affected by a myriad of factors such as religion, past animosity or gratitude, shared or conflicting beliefs, blood relations, and so on and so forth. Going through this information allows a player to construct a cause-and-effect for events happening in the game, and weave an intriguing “plot” in his or her head.

Emergent Narratives

Jenkins described emergent narratives as stories that are “not prestructured or preprogrammed”, instead “taking shape through the game play”. Games that lend themselves to the creation of such stories tend to be “a kind of authoring environment within which players can define their own goals and write their own stories.”

This is an oft-repeated description of Paradox’s games, even by our own developers. Players have been telling stories created by their experiences with grand strategy games for as long as the genre has been in existence. Here’s an excerpt from a retelling of a Crusader Kings 3 play-through on Reddit:

“First, his regency council had to deal with upstart English rebels, muslim invasions and traitorous vassals seeking secession. This taught young Filip that the only way to deal with troublemakers was to remove them. So, when he came of age, he began locking up all those vassals who had wronged him during the regency years, discovering along the way he had a morbid fascination with torture. The South remembers. He would also make sure to murder anyone who made fun of his lisp, often times losing his temper instead of carefully planning out the victim’s abduction as usual.”

In fact, it was these types of stories that got me interested in Crusader Kings 2 in the first place. Listening to a colleague describing his session made it feel like it was a game where almost anything was possible, and remarkably, that’s not too far from the truth. Emergent narratives have always been, and always will be, the mainstay of grand strategy titles.

What does this mean?

Of course, after all that babbling, I needed to ask myself what it all means for the design of grand strategy going forward. Design theory is definitely interesting in its own right but I’m personally looking for insights that are more prescriptive. Here are a few takeaways I harvested from this entire thought exercise.

Lean Into Existing Fantasies

Popular culture and history are the reason why theme parks, museums and environmental storytelling in general, works. It’s the fantasy we bring with us as players into these narrative worlds that glue the disparate elements together and weave them into coherence. If these games featured original new worlds, it would be dramatically harder to do that.

It could be the reason why The Scientific Gamer thought that Endless Space 2, Stellaris’ closest galactic-empire-building competitor, “sucks at building the emergent story of your empire’s growth”, even though it had incredibly detailed races, complete with voice acting and unique mechanics. Here’s an interesting excerpt from the review:

“If nothing else, Endless Space 2 has at least let me figure out what bugs me about the series. It’s not that the various empires don’t feel distinctive or characterful, because they do. They just don’t feel like my empires.”

Sandbox games need to give the player space to create their own interpretations of the unfolding events, not force their version of it down player’s throats. The only way for developers to do this is by presenting a sandbox that is compatible with player-driven fantasies, ergo, building it using familiar material from popular culture and history.

Player Agency As Narrative Functions

One of the points Jenkins brought up in his text was that in successful sandbox games like the Sims, interactions with the game world was limited to “only a small number of artifacts, each of which perform specific kinds of narrative functions”. He further elaborated that this limited but descriptive player agency allowed players to better form interesting stories in their minds, in his words:

“Newspapers, for example, communicate job information. Characters sleep in beds. Bookcases can make you smarter. Bottles are for spinning and thus motivating lots of kissing. Such choices result in a highly legible narrative space.”

Compared to action adventures and role-playing games, which are filled with forgettable interactions such as killing enemies and picking up items, interactions in grand strategy games are much more narratively significant. Sending your marshal to curb dissent in faraway territory, marrying your eldest daughter off to a neighboring liege, or ordering the execution of your wife, are all possible actions you can take in a routine game of Crusader Kings 3, each filled with enough narrative juice to power the most elaborate of emergent stories.

Events As Cornerstones Not Bricks

Jenkins referenced urban designer Kevin Lynch’s book The Image of the City in his essay. He quoted Lynch talking about the need for city planning to create spaces that make activities within “narratively memorable”, but to be careful not to over-decorate, commenting that “a landscape whose every rock tells a story may make difficult the creation of fresh stories”.

Applying the essence of that statement to grand strategy design, beautifully written events lend a lot of intrigue and plot twists to the player’s emergent narrative, but too much of it can stifle the player’s creativity. Events can be amazing prompts, but ultimately we need to give the player space to finish the stories on their own. Only then can the empire be truly theirs.

Conclusion

Everyone I ask has a slightly different definition of what a grand strategy game is, so I definitely think as developers we can dig a bit deeper and understand this genre a little more. Arranging the elements to fit into the sockets of Jenkins’ essay framed the notorious tooltip and pop-up presentation of Paradox’s flagships as a kind of textual level design. I have never thought of them that way before. Consequently, it intrigues me if more level design philosophies could work on the sea of glyphs that fill our galaxy ruling screens. We’ll see.